Francis Potter

Brain tumour survivor, transgender awareness advocate, proud Aspie, guitar dabbler, musical theatre nut, Pythonista, MotoGP follower, husband, father, Canadian, recovering perfectionist, skeptical contemplative Anglican, and resident the traditional territory of the Lək̓ʷəŋən people

Surviving a brain tumour

In the early evening of November 10, 2022, in a small room in the emergency area of North Island Hospital Comox Valley, a doctor entered and showed me a picture of the inside of my brain. My world changed in an instant...

A vision of static

Colours appeared less vibrant, as I had noticed in the store. But I also saw static — like an old-fashioned television with a broken antenna — across my entire visual field, distorting everything...

The importance of dark mode

Consider using a dark background for presentation slides and other applications that support it. You might appreciate giving your eyes a break, even for everyday work, and it would certainly help when sharing with me...

The Transformation Architect

Rooms buzzed with creative energy and enthusiasm as individuals broke from their daily grind to brainstorm and collaborate in a deep, powerful way. Frank unleashed the genius within every individual in the otherwise boring corporate environment, as ideas flowed...

"Selling is so easy!"

Evan turned, looked me in the eyes, grinned from ear to ear, and shouted — SCREAMED at me — “I am by far the BEST EVER!!”...

Professional values

While attending Carnegie Mellon University in the late 1980s, I attended two on-campus presentations by author Kurt Vonnegut. At the time, the university received large research grants each year from the US military...

Professional background

Empowering software organizations to achieve peak performance and cultivate generative cultures through AI-driven workflows, end-to-end automation, and robust application security...

Surviving a brain tumour

The story of my brain tumour and recovery experience, adapted from an email sent to family and friends, January 2023

In the early evening of November 10, 2022, in a small room in the emergency area of North Island Hospital Comox Valley, a doctor entered and showed me a picture of the inside of my brain. My world changed in an instant.

The story started while living in oppressively hot Santa Clarita, California with my wife and her teenagers. We were married in 2020 in a tiny backyard ceremony with only two guests, moved to Canada two years later, settled in a gorgeous small town on Vancouver Island called Courtenay, and bought a house.

During the same period, I made 5 visits to England to visit my dying aunt Jane. I retrieved her from the hospital in 2020 and brought her to our decades-old family home in Wolverhampton, near Birmingham. I then helped her take a place in a top-quality care home nearby, where she stayed until she died surrounded by lifelong friends in March 2022. I organized and spoke at Jane's funeral, and cleared out the house for sale.

Feelings of lethargy and laziness increasingly took hold, both in England and at home in California. I attributed my condition to the COVID environment, the weight of travel, the sadness of working with my dying aunt, getting older, bad habits, and life stresses. Still, I ended up having to leave my job, and could barely function at home.

Hoping that the move to Canada would provide a fresh start for me, I enjoyed our arrival. But decline continued. I had memory lapses; the month of October 2022 has more or less disappeared from my memory. Headaches recurred every day. I had a dizzy spell in the public library and fell on the floor. One day I walked around in a daze for hours, unsure where I was, in my own home. But still we couldn’t identify the problem, and nor could doctors.

In November the headaches became more severe early in the mornings. I read Wikipedia.com, and learned a little about brain tumours. The descriptions of headaches and other symptoms uncannily seemed to match, and I knew the time had come to take the problem seriously, whatever it was.

My wife drove me to the hospital, where the doctors finally performed a CT scan, then diagnosed the tumour, immediately began treatment and scheduled emergency surgery.

The surgery succeeded. The tumour is gone.

I’m lucky. Meningioma is a slow-growing type of brain tumour, different from the glioblastoma that kills so many people. One surgeon said it had probably been growing inside my skull for “years”, which explains why the symptoms seemed to accumulate so slowly. If the surgeons missed a crumb, it could grow back, probably just as slowly. So I will be receiving follow-up MRI scans, possibly for the rest of my life, to keep an eye out for recurrence.

In addition to the surgery, I received a 3-week steroid treatment (Dexamethasone), which prevented me from sleeping, giving plenty of time to think about the past and the people in my life. I also enjoyed long, rich conversations with my wife, sometimes through the night, about our life together and hopes for the future. A pleasant kind of emotional healing took place.

A physical therapist helped me re-learn to balance, walk, and climb stairs. Family and friends provided immense levels of support. It took faith, courage, and patience, but I finally felt ready to re-enter the social and professional world about 6 months after the diagnosis and surgery.

See A Vision of Static about the permanent vision impairment that followed the brain tumour experience

A vision of static

The story of my vision impairment, adapted from an article written for the Visual Snow Initiative

Shortly after arriving in Canada in 2022, I walked into a store, and everything looked greyish. Colours still existed, but seemed somehow muted or less vibrant. Perhaps the store had chosen cheap lighting, I thought. Or my eyes had to adjust to the oncoming winter. Or I needed new glasses. In fact, I had experienced the first hint of my journey with "visual snow".

Visual problems appeared on my list of complaints when I entered the emergency room about 3 months later, along with severe headaches, mental confusion, dizziness, and memory issues. “Meningioma” they called it: a type of brain tumour. Four days later, a surgeon removed the tumour, and the long recovery began. But things went sideways quickly. After I came home, my vision started to decline rapidly until, on Christmas eve, I returned to the hospital for a follow-up scan. Apparently, my brain had started a healthy healing process, and everything would work out fine.

But the problem persisted. Colours appeared less vibrant, as I had noticed in the store. But I also saw static — like an old-fashioned television with a broken antenna — across my entire visual field, distorting everything and bringing a kind of unwanted activity to even the calmest views. Reading became nearly impossible, especially on paper or white backgrounds, and I struggled to recognize friends in crowded rooms or see pedestrians on the road.

My condition stumped doctors. The neurosurgeon said he had operated in the front of my brain, far from the visual cortex, so I must have an eye problem. The optometrist prescribed new eyewear and claimed he had returned my vision to 20/20. The ophthalmologist saw "no evidence of acute eye disease" and asked me to return in a month. The oncologist said things happen, and I ought to find a new career since I might have a hard time working with computers ever again. My family doctor shrugged.

Confused, lonely, and scared, I finally phoned a family friend who had retired from his optometry practice (and patent-earning optometric research) decades ago but still knew a thing or two. Within five minutes, he told me the technical name of my condition: “visual snow”.

The physical snow had begun to pile up outside in the Canadian winter when my wife drove me for over an hour to see the nearest neuro-ophthalmologist (yes, that is a real profession, as I learned). The doctor explained -- as I had already read -- that my condition had no cure. He prescribed a medication to try (useless, I learned online before declining to take it) and petitioned the province to revoke my driving license for safety reasons.

Determined to figure out a way forward, I dove into online research, my laptop set to light-on-dark text, the only way I could read. I learned that visual snow is widely misunderstood, often misdiagnosed, untreatable, and usually permanent. The biggest impact for many of us is depression because of the dissociation and isolation that comes from losing visual sense. I decided to keep my family and friends close, practice adaptive strategies, and maintain a sense of hope.

Then the Visual Snow Initiative appeared in my web browser. I felt moved as I read the web site and watched the founder's TED talk. Finally, it seemed that someone understood. Based on the work of the Initiative, I underwent a course of vision therapy, which did little to diminish the static in my visual field, but helped me develop confidence and function better in the new world I occupy.

Did the brain tumour cause my visual snow? Or the surgery? The powerful 3-week steroid treatment? Some combination of them? Or pure coincidence? I will always wonder. The day the doctors diagnosed my brain tumour seems like a rebirth to me, and I plan to celebrate and enjoy my second chance at life, even with all this static in my view.

See the importance of dark mode for how you can help

The importance of dark mode

An appeal to professional associates, first posted to LinkedIn, March 2023

Survivor

In November 2022, doctors diagnosed me with meningioma - a "benign" form of brain tumour. Four days later, surgeons removed it. My functional and professional abilities returned after recovery, but the tumour and surgery left me with a persistent mild visual impairment.

I see the world 24/7 through what looks like a transparent layer of white static, like a mistuned analogue television. Neuro-ophthalmologists call the condition "visual snow". It's probably permanent.

The impairment has a minor impact on workplace interactions, and I appreciate accommodation by colleagues and associates.

What is dark mode?

Most people spend most of their screen time working on a white background.

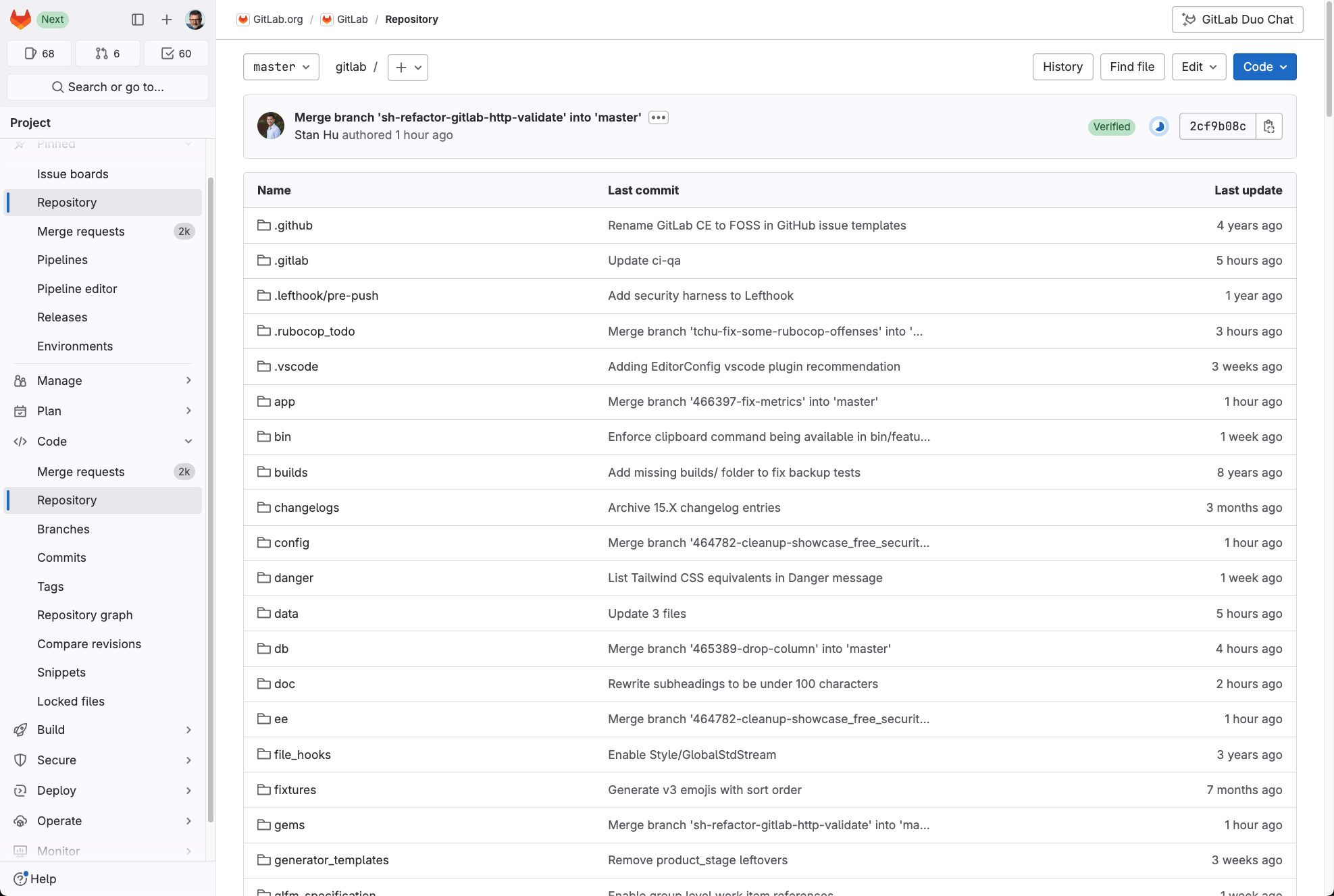

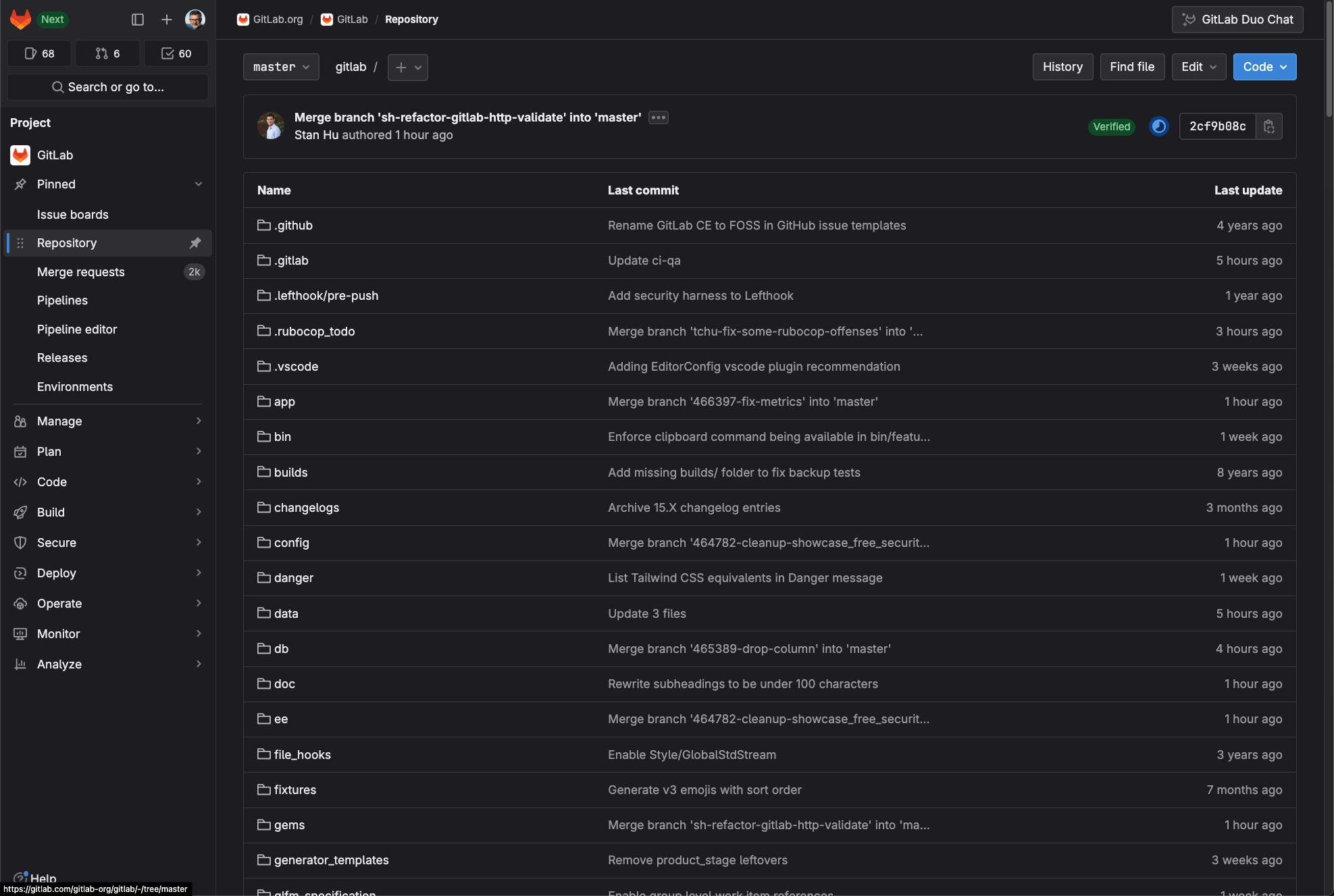

The view shown above blinds me, slows me down, and causes traumatic headaches. "Dark mode" works much better.

I've found that many people prefer "dark mode" but for me, it's necessary for productivity and health.

How to help

When sending a screenshot or sharing your screen on a Zoom call, please consider setting up dark mode ahead of time.

You might appreciate giving your eyes a break, even for everyday work, and it would certainly help when sharing with me.

Chrome extension

The Dark Reader Chrome extension works well, and has plenty of settings for sites with different types of CSS stylesheets. If you install the extension, but prefer to use light mode for daily work, just turn it off until our next call.

Dark Reader automatically detects dark mode in site and apps that already support it (such as GitLab), so you can take advantage of app-specific dark mode design when available.

GitLab

Turning dark mode on and off in GitLab is easy. Follow these steps:

- Click on your profile photo near the top left of any page

- Choose "Preferences" (or click here while signed into GitLab.com)

- Under "Appearance", choose "Dark (experiment)"

- Under "Navigation theme", choose "Neutral"

- Under "Syntax highlighting theme", choose "Dark"

Presentations and more

Also consider using a dark background for presentation slides and other applications that support it. Other techniques include:

Some other possibilities:

- Dark theme in Chrome itself

- Dark appearance setting in MacOS

- iTerm offers a dark appearance option

Most of the settings described above work in similar ways on other operating systems, browsers, and terminal emulators.

I deeply appreciate all the support I've received from my professional community since the surgery. Thank you.

Note to designers

Web and UI designers, take note! The extra effort put into "accessibility" makes a real difference to some users. For example, test your web app with the Dark Reader extension to make sure UI controls remain visible. If you want some free feedback on your site and application designs from someone who needs the accommodation, just let me know.

See Surviving a Brain Tumour for the whole story

The Transformation Architect

"Training Coordinator" sounded like a mundane job title for a university engineering graduate, but I embraced the role with curiosity and drive. Some of the "training" I coordinated covered technical topics (what substances corrode stainless steel?) while most touched on "soft skills" — professional writing, team building, effective meeting management, the "psychology of achievement", and so on. From sitting in the backs of classrooms for a year, I gleaned many tips and tricks that have helped me master a variety of situations throughout my professional life in engineering, management, and consulting.

But even better, I got to work with a man named Frank.

Together, Frank and I formed part of the "Total Quality Management" group at a large global corporation. TQM had taken the business world by a storm following the well-documented success of Toyota in the automobile market, and businesses worldwide tried to emulate their approach. An internal consultant nearing retirement, Frank took me under his wing and let me shadow him during my year on the team.

Frank advised executives throughout the company who struggled with business challenges, from simple questions ("too many people taking sick days") to large, demanding projects ("we missed our production targets last quarter"). Often, Frank's "customers" expected answers. They wanted a quick fix, a ready-made solution, or justification for a tough call. They hoped Frank would tell them who to fire, how to justify workload increases, new purchases to authorize, or what new procedure to dictate.

But Frank had different ideas. As a champion of organizational change, he believed that the best decisions and most effective changes come from inside. "Whoever shows up for a meeting," Frank would say "is the right group of people. Inspire them to bring their best thinking, and facilitate an effective decision."

That year, I learned that, to meet the challenges of changing markets, business conditions, and demographics, organizations must change constantly. And that change must happen across 5 dimensions, often in parallel. Conveniently, the titles all start with "S".

- Strategy: Clear goals and objectives combined with meaningful organizational values

- Skill: Knowledge and abilities of individuals

- Styles: A generative culture that fosters both autonomy and collaboration

- Structure: Appropriate job titles, reporting relationships, and incentives

- Systems: Tools and technology that underlie successful processes

Need to set a new direction? That's a strategic change. The group might need new skills to implement it. Want to fire someone? That's structure, but watch out for communication style gotchas. All five dimensions matter.

With each internal "client", Frank started by scheduling a transformation workshop with a cross-section of the team. He showed up with a simple poster covering "ground rules" and a loosely defined process. Then he started facilitating -- neither instructing nor simply watching -- a profound process of brainstorming, refinement, prioritization, and, ultimately, design for new versions of each of the 5 S's.

Rooms buzzed with creative energy and enthusiasm as individuals broke from their daily grind to brainstorm and collaborate in a deep, powerful way. Frank unleashed the genius within every individual in the otherwise boring corporate environment, as ideas flowed. He gently facilitated the process, nudging the group toward active listening, thoughtful prioritization, and ultimately the definition of a better organization for themselves. He believed that, with the right guidance, teams could overcome challenges most effectively through grassroots transformation.

The process worked. Entire corporate departments accomplished goals they had set out for themselves, executives kept Frank's number on "speed dial" (consider the era), and ultimately the corporation continued to dominate its industry over the successive decades.

Years later, "Six Sigma" replaced TQM. Then, as enterprise software transformed the world of business entirely, agile and lean methodologies became popular. I've read many of the books and seen the newer techniques in action. Despite changes in technology, culture, and language, the principles that I learned from Frank remain timeless.

- Organizations can change to meet new challenges and expectations (or even exceed them)

- The best people to drive change are the people doing the work - from all levels

- Effective techniques of advice, facilitation, and coaching can have an impact on outcomes

- Keep the 5 S's in balance throughout the process

Frank retired, and died shortly thereafter. I moved on to the next stage of my career. Years later, after moving through various roles as individual contributor, manager, and consultant, I decided to practice techniques and adopt values learned from Frank no matter what job title I hold. For myself, my colleagues, and my customers, I hope to facilitate lasting multidimensional change in the hearts and souls of organizations the way Frank demonstrated all those years ago.

"Selling is so easy!"

Originally published on Medium in Sep 2016

“The new sales guy is here,” said the CEO.

I’d been managing the engineering team at a San Francisco tech startup for a couple of years. We had customers, but sales were slow, and the CEO had decided it was time to up the game, so he hired Evan.

“You must be Evan,” I said politely when I first met him, putting on my best warm smile and extending my hand for a firm shake. “How are you?”

Like most engineers, I saw sales and marketing people as aliens whose presence in the technology world had to be tolerated. Sales, to me, was for people who weren’t smart enough to code, and who brought unreasonable demands and stupid questions to the engineers who did the “real work”. I had a pretty bad attitude.

Evan turned, looked me in the eyes, grinned from ear to ear, and shouted — SCREAMED at me — “I am by far the BEST EVER!!”

“All style and no substance”, I thought. And Evan’s style was outrageous. He shouted in almost every conversation. He ate only vegan food, attended board meetings barefoot, and cold-called CEOs of Fortune 500 companies for sport. He also told me that engineers could become incredibly successful salespeople, if we could just get over our attitude. I firmly disagreed.

I assumed Evan would fall short of expectations and disappear. But within a quarter, our company’s typical deal size had increased a hundredfold. So I decided to pay attention. Maybe I could learn something.

Evan had pitched our services to a midwestern manufacturing firm, and two representatives from their marketing department came to the Bay Area to check out our capabilities in person before sealing the deal. I offered to join the group taking the visitors out for dinner.

“Where are we going?” I asked Evan, expecting one of the nice seafood restaurants near Pier 39, or perhaps an Italian place in North Beach.

But Evan had a different idea. He insisted we take the midwesterners to Cafe Gratitude, the new age vegan restaurant, in the middle of what some considered a tough neighborhood, with rainbow murals on the walls, feel-good board games on the tables, and staffers standing on chairs reading a manifesto of peace.

Evan had a great time, but our guests hated the decidedly unbusinesslike atmosphere. “What are we doing here?” they asked nervously as casually dressed young people greeted us with hugs and servers brought plates of strange salads with stranger names.

As we left the restaurant, I pulled our valuable prospects aside and whispered quietly, “sorry about this… you can order a hamburger from room service when you get back to your hotel… it’s OK.”

We thought the deal was lost.

In fact, Evan closed the deal, and I was hooked. What did this guy know that I could learn? Was it true that I could learn to close big deals, while maintaining my engineering mindset and smarts?

When I relaunched The Hathersage Group last year, I decided to seek Evan out for advice on how to sell my services better.

I flew back up to San Francisco, rode BART out from downtown, and walked to the graffiti-covered warehouse where Evan runs a new venture-backed startup. I waited patiently in the lobby, which doubles as the web site tech team room. I brought an offering for the master — fresh vegan chocolate treats from Cafe Gratitude.

When finally ushered into Evan’s cluttered chamber, I sat down, took out a piece of paper, looked him in the eye, and said “I want to learn how to sell. Tell me what to do.”

“Oh Francis!” he said with a grin. “Selling is so easy!”

Evan gave me ideas to consider, books to read, and exercises to do. I wrote down everything he said, and followed his guidance to the letter.

So far, the results have been amazing. My company’s relaunch surpassed my wildest expectations. Business is booming, and the future looks bright.

Based on my experience, I believe that engineers can learn how to close deals — not as slimy “sales guys”, but as professionals with deep integrity. And we can have fun doing it too. It just takes a desire to learn new ideas and dedication to developing and practicing new skills.

And, of course, it takes a good attitude. Every day has to be the best day ever.

See Tips for engineers entering sales

Tips for engineers entering sales

The "10 Rules of Selling" I wrote down after working with a guru:

- Greet every day with love in your heart

- Have an audacious purpose and force yourself to believe in it

- Be interesting ~ never talk about what you're selling

- Know more about your customers' business than they do

- Always start with the CEO

- In all cases, take the boldest path

- Stay calm when others become uncomfortable

- Find out where the line is by crossing it

- Kiss ass

- Sell high

My reading list for engineers (or really anyone) entering sales:

- Power Questions (Sobel, Panas)

- Getting to Yes (Fisher, Ury, Patton)

- How I Raised Myself… (Bettger)

- The Seven Habits… (Covey)

- Mindset (Dweck)

- Clients for Life (Sobel, Sheth)

- Never Eat Alone (Ferrazzi, Raz)

- How to Work a Room (RoAne)

- Think and Grow Rich (Hill)

- The Greatest Salesman in the World (Mandino)

Professional Values

While attending Carnegie Mellon University in the late 1980s, I attended two on-campus presentations by author Kurt Vonnegut. At the time, the university received large research grants each year from the US military to conduct research in support of the Reagan-era defence buildup. Vonnegut pleaded with students to adopt an ethical standard in their careers, even going to far as to suggest creating the equivalent of a “hippocratic oath” for engineers, and specifically to refuse work in the military sector.

Inspired by this call to ethical practice, I started my career guided by strong values and social responsibility. Shortly after graduation, I worked for several years in the international social justice sector, including service to community organizations on the ground in Southern Africa. Since joining the tech sector, I've strived to cultivate relationships with organizations and clients whose missions align with my core principles. Specifically, I actively seek to work with others who:

- Commit to environmental stewardship and sustainable practices

- Champion diversity, equity, and inclusion, especially toward women, international populations, and LGBTQ+ individuals

- Work to build a more just and peaceful world through innovation, education, and social progress

My standards reflect years of thoughtful consideration about how my skills can best serve society. This approach has led to deeply meaningful collaborations that advance technical excellence, social good, and personal fulfillment.

Professional Background

Driving solutions to real-world problems through direct engagement with sophisticated customers. Building tech that outlast my involvement. Advancing adoption of technologies that genuinely improve how people live and work. Too technical for pure sales; too extroverted for pure engineering.

As a Senior Technical Architect with GitLab Professional Services, I engage with high-profile enterprise customers to facilitate the transformation toward the higher levels of productivity and quality provided by agentic engineering.

Meanwhile, I maintain commitment to the software engineering fundamentals that help organizations to achieve peak performance - generative culture, thorough testing, end-to-end automation, and robust application security.

Previously roles included Senior Solution Architect (presales), Product Marketing Manager (competitive intelligence), and Senior Professional Services Engineer. I first joined the GitLab team at the beginning of 2019.

Before GitLab, I ran an independent professional services firm after serving for years as senior engineering manager and product manager for various tech startups. My career has touched the worlds of content delivery (CDN), marketing software, wealth management, commercial media, social media, language translation, financial services, and transportation.

Visit my LinkedIn profile (below) for a complete professional history.

Software ↗

"SteamWiz Labs", a collection of command-line personal productivity tools that help life go a little more smoothly (developed by me independently)

Video portfolio ↗

A variety of conference talks and explainer videos on technical topics, mostly about GitLab and DevOps, with some AI and ML

LinkedIn profile ↗

Decades of diverse experience in the universe of computing technology

External content

- SteamWiz Labs - A collection of command-line personal productivity tools that help life go a little more smoothly

- Busy - "Personal time management for techies" - a CLI todo-list tool I developed during downtime and use every day

- WizLib - Framework for command-line devops and personal productivity tools in Python

- Video portfolio - A variety of conference talks and explainer videos on technical topics, mostly about GitLab and DevOps, with some AI and ML

- LinkedIn profile - Decades of diverse experience in the universe of computing technology

- ProCICD guide - A notebook of CI/CD best practices developed to meet a series of personal and professional requirements

- ProCICD base library - Patterns and conventions for organization-specific CI/CD libraries

- My GitLab profile - Reflects personal projects and contributions

- Paul Strasburg and the history of IDEX - Content developed for a 1996 fundraising event for a favourite social justice organization

- Sally - My mother's memoirs, published as a paperback book